The End of Neoliberalism

Because of the fact that markets are already in summer mode, I want to discuss a topic with a more philosophical and economic background today: Liberalism, respectively, the crisis of liberalism that we face these days.

Whether we revert to fundamental liberal principles will definitely play a role in how our economies will perform in the future. However, the current zeitgeist suggests that politics, with democratic legitimacy, will take a different path or has already taken it.

During its history, proponents of the liberal theory have always compromised by accepting social democrats and interventionists. While the intent is understandable, it has not convinced the general public that liberalism (economically and socially) is the right way to choose.

Additionally, the liberal idea is not an idea that is inspiring young people. Most youths praise an interventionist, socialist economic model, whether one calls it Lifestyle-leftism (Sara Wagenknecht) or democratic socialism (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez or Jeremy Corbyn).

The idea that the state should more and more intervene in our economic and social life is gaining proponents on both sides of the political spectrum. While this phenomenon is not new, it raises the question of why a majority is now rejecting an economic and social system that has led to a world where economic wealth is higher than it has ever been.

A further observation leads to the conclusion that the main reason liberalism is in a deep crisis may have been shown during the last crisis of liberalism when the majority of liberalist thinkers implemented the neoliberal doctrine. In my opinion, this has led to the foundation for the current state of liberalism as it is today.

Nowadays, many people mistrust liberalism because they have found that certain groups benefit more from the current system (neoliberalism) than they do themselves. Because they do not know better, they think that this system is economic liberalism and overlook the fact that, in reality, we live in an era of socialist, neoliberal interventionism.

The liberal idea has been under pressure from the beginning. In the 19th century, the rising workers' movement (or more precisely its wealthy, intellectual leaders) called for government interventions to correct some of the free market system's results that they considered unfair. Back in those days, Manchester liberalism, which rejected state intervention, was seen as the reason why so many industrial workers lived in abject poverty.

Undoubtedly, the conditions under which many families had to live during this period were devastating, but this was mainly because the economy suddenly had to support more than twice as many people as before. No other economic system other than liberalism would have been able to cope with this enormous task.

Due to the limited demand for labor in the rural areas, masses of people poured into the cities, where they hoped to find jobs within industrial production. In doing so, they were ready to accept working conditions, no matter how bad, as long as it saved their families from worse.

Clearly, the demands of the socialist trade unions and parties could only be financed because of liberalism and liberal economic policy, which continued to raise the average standard of living. However, these demands mainly were enforced by the already politically established forces, who hoped to push back socialist movements.

For example, people like Otto von Bismarck, for instance, were ideologically as far away from the idea of liberalism as, let us say, Karl Marx. I do not even want to evaluate whether state health insurance is a good or bad thing or whether a private company could not offer the same service better and cheaper because this would clearly go beyond the scope...

Although, before Bismarck implemented state social security, the unions were already offering private insurance benefits for their members. From a liberal point of view, there would have been no objection to this on the one hand, and on the other hand, a free market for social insurance, as all free markets, would have resulted in the best service being offered at the best possible price. However, the political interventionists had other plans.

After all, the nationalist political right in the German-speaking area was hardly less interventionist than the political left. The only difference was (or still is today) that right-wing parties were interested in maintaining the status quo, while left-wing parties wanted a “better world”. While the right used interventionism to serve their purposes, the left tried to use it to enforce their well-intentioned changes. But the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and liberalism was the way to fight both of them.

Both sides, however, enjoyed distributing money to groups that were politically close to them through an expansion of the money supply and taxation. It should not be a coincidence that the Weimar hyperinflation was fueled by nationalist allies, who were close to the beneficiaries of this expansion of the money supply (large-scale German industry). During this time, distrust of the liberal economic order grew, and people longed for a state system of economic interventionism.

After the roaring 20s ended abruptly because of the speculative bubble bursting on Wall Street and an economic depression set in, interventionism finally gained the upper hand in both the New and Old World.

Whether in the United States, Germany, Italy, Great Britain, or France: Attempts were made to combat the crisis through more interventionism to bring the economy back to growth. Instead of reducing unemployment and production by adjusting wages, it was combated with a general devaluation of money. The gap in goods production created by the crisis should be closed by the state to fight unemployment.

All of these programs were in place when the most famous economic work of the 20th century, The General Theory of Interest, Employment and Money, was published by John Maynard Keynes in 1936. In fact, Keynes did not present a new proposal for the design of the economic policy. No, in retrospect, he only provided the theoretical foundation for an economic system that has already been practiced.

Liberalism was in a deep crisis, and many proponents were well aware of it. Therefore the American lawyer Walter Lippmann gathered some of the leading liberal economists of the time (including Friedrich August von Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Wilhelm Röpke & Louis Rougier) in Paris in 1938 to discuss how to revive liberal ideas.

The majority of the participants agreed that a departure from the laissez-faire principle was necessary to make the liberal idea attractive to the general public. Wilhelm Röpke and Alexander Rüstow, in particular, have believed that economic interventions have to be accepted in some cases to keep the idea of economic liberalism alive for a long time. At the same time, classic liberals such as Hayek or von Mises largely rejected such ideas.

Commonly, this meeting is seen as the birth of neoliberalism. Except for a brief period after the fall of the communist Soviet Union, it should mark the beginning of the end...

After the Second World War, Friedrich August von Hayek tried again to establish a liberal alliance between the new and old liberalism representatives when he founded the Mont Pelerin Society. However, he was not that successful. At the first meeting, it became evident that the representatives of the laissez-faire approach were in the minority, and this time, Ludwig von Mises was not on honeymoon...

During one of the debates, Mises, the classical liberal, left the room furiously and called the other participants, including Wilhelm Röpke, Walter Eucken, and the young Milton Friedman, a bunch of socialists. A few years later, Hayek also hardly played a role within the Mont Pelerin Society and the participants who proclaimed the third way: A liberal system, in which the state intervenes in certain areas of the economy. This system was most famously implemented in Germany in the so-called Soziale Marktwirtschaft (social market economy).

All over the world, interventionism was moving forward in the following years: Allegedly to protect workers' rights, domestic producers, farmers, or to protect consumers or other certain groups: Some reason for more and more government interventions was always found, and the third-way advocates supported many of these economic interventions.

One can agree that the third way supposedly kept many parts of the free market system free from interventionist policies than they otherwise may have been. Sadly the ordoliberals failed to stop it over the years as the future generations have become more open to interventionist policies.

When President Richard Nixon broke the gold link to the US dollar and ended the Bretton Woods system in 1971 because the US had put far more dollars in circulation than was backed by gold, this policy played a special role in the triumphant march of interventionism.

This completed the step towards an international financial system that gave interventionist monetary policy a free hand. Since politics was in charge to install the people at the top of central banks (the ruling politicians were always interested in using interventionism to provide their voters and groups close to the party with election gifts), it was already a done deal at that time that politicians would adopt this to make use of the new monetary system.

While the liberal worldview has been able to record one victory after another in social life, such as the legal equality of women and family models apart from the classic marriage between men and women, economic freedom has been further decimated.

It is also painful that this social progress was not achieved by the neoliberals, but by left-liberal groups, and as such in the most anti-liberal way: Instead of freeing private life from the influence of the state and from politics, as it would have been required from a liberal point of view, new laws were passed that politicized and regulated private life. In my opinion, this step contributed to an ever-increasing polarization (if one assumes that one supports the thesis that this happened, which is not entirely clarified).

Despite all sorts of interventionism, which were partly approved by Ordo-Liberals (who have become a new version of the Kathedersozialisten (catheter-socialists, eng.)), the third way, or restrained capitalism, led to a massive gain in the prosperity of large part of the world's population. As long as this trend continued, no one really questioned this combination of capitalist and socialist policies.

After the Soviet Union finally collapsed, as von Mises correctly predicted back in the 1920s, many third-way advocates thought that interventionism could now be pushed back. In trying to do so, they overlooked how far they had already pushed interventionism by themselves.

Instead of giving the consumer a choice to decide on the quality of an offered good or service, more and more market entry barriers for the production of goods and services have been introduced under the guise of consumer protection, which in the end, as always, was also welcomed from the conservative side as well because this protected already established companies from competition in the market place. Neoliberals mostly came up with an excuse for why such policies were not that bad and helped the economy move forward.

Those companies, in particular, benefited from an expansion of legal requirements, hygiene regulations, and other regulations, which further undermined the responsibility of consumers and hindered the trade in goods and services. The striving for individual and economic liberty, a basic requirement for a classically liberal society, was thus made more difficult.

I suspect that a large part of the population would have come to terms with even with that interventions, as economic progress continued and made many things possible that would have been unthinkable 40 years ago. Only because of innovative forces of this residual liberalism (which were still in play) it was possible to compensate for lost jobs in industrial production, which had emigrated to the Far East in the course of globalization.

The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 marked a turning point in history: On the one hand, some of the people rediscovered the theses of a genuine, liberal (laissez-faire) economic system (which would not have been possible without the internet, which now provided access to the ideas of classical liberalism), but on the other hand to a further expansion of interventionism as an answer to the economic downturn.

Under the great influence of the intellectuals, who have always been advocates of economic interventionism, it prevailed that in the eyes of the majority of the population, it was neoliberalism, a system that they considered as one which promotes the unhampered market economy, has triggered the financial and economic crisis.

The role of the rating agencies, who had provided the securitized junk loans with triple-A ratings and are still strongly protected from competition by the US government, was turned around by the interventionists: This shows that the capitalists (who, as in Weimar times, had more of an interest in interventionism as in free markets) make the rules, so their argument goes. What is overlooked by them is that it is always state interventionism that makes these things possible. Those are the ones who make the rules.

Then the more liberal mainstream economists committed their biggest mistake in recent history: In contrary to the opinion of classical liberalism, according to which everyone has to bear the consequences of one's economic actions, they propagated that the state has to intervene (very similar to the Keynesian doctrine) in this crisis to save the economy.

Privatizing profits, socializing losses! was the reproach by the interventionists to the neoliberals, and rightly so. The attempt by mainstream economists to justify these economic interventions to the general public failed miserably.

The solution they proposed for overcoming the economic crisis, a (temporary) expansion of the money supply, led to the fact that precisely those, who had previously brought themselves into problems through risky economic behavior, benefited, while the broad masses, apart from maintaining their jobs, fell by the wayside.

If the crisis had been allowed to run free, as in the 1920 depression in the United States (you may never hear of this crisis, because it was over so quickly), a transformation to a more agile and sustainable economy could have been accomplished. If one had tried to clarify this to the population, it might have been possible for them to get their support for this, presumably short, difficult period.

It is no coincidence that things like cryptocurrencies have been enjoying increasing popularity since the 2008 crisis because people are looking for alternatives to the zero interest rate trap (Ronald Stoeferle, Mark Valek, Rahim Taghizadegan) as they increasingly anticipate that they may not be able to maintain their standard of living into old age with public pensions payments only.

People feel that their economic situation did not improve during the 2010s, while stock markets climbed from one all-time high to another. They notice that the economic policy pursued by the interventionist governments no longer serves to increase their standard of living but rather enriches wealthier groups, who were able to expand their economic prosperity further and further.

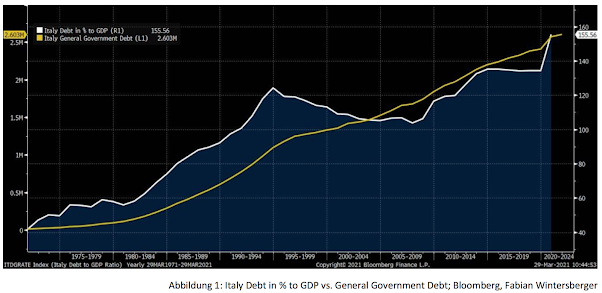

The claim that countries can grow out of their ever-increasing debt did not come true again. As the debt increased, the level of economic growth continued to decline. Additionally, as always, hardly any government later cut back on its expenditures. They never do, and neoliberals should know that.

It became evident that instead of returning to liberal principles, the neoliberal movement failed to stop further economic interventions. They back interventionism when it is implemented and then wonder why governments do not end them. This is true for the macro-and the micro-sphere.

For example, an increasing number of articles were published where economists demanded that politics - similar to Scandinavian countries - should expand childcare and make it affordable so that mothers (who still do most of the childcare, at least here in Austria) ideally would be able to return to full employment as early as one year after the birth of the child. Instead, no neoliberal even questions the regulations within this certain market.

Moreover, on the one hand, it is still a highly personal decision within a family how they organize childcare, and on the other hand, it could be expected that, if childcare prices would really be that high in an unregulated market, a free market solution would be even more desirable. In a free market, many different childcare models compete for potential customers, and the best model that fits the demands of families wins.

Thus it can be stated that neoliberals continue to call for interventions under specific circumstances, although governments never cut back on it. This shows the crux of neoliberalism: The result of voluntary economic cooperation is accepted by mainstream economists only if they are satisfied with the results because they pretend to know better what is good for people than they do themselves.

At the macroeconomic level, interventionist expansion of the money supply to combat the economic downturn caused further wealth inequality. Because of that, many interventionists on the left side of the political spectrum now call for a wealth tax, which would only mean combating symptoms, as the neoliberal representatives of the main economic stream correctly recognize and therefore correctly are against it. This is a wonderful example of von Mises's Oelflecktheorem (also known as the cobra effect), according to which one market intervention always leads to further interventions because of unintended side effects.

Anyone who hoped that liberalism would have a comeback at the beginning of the new decade was bitterly disappointed: This time, the corona pandemic caused a further intensification of interventionism.

And again, especially the neoliberals called for another round of state interventions as most of them supported lockdown measures to combat the virus. However, the effectiveness of such measures has been highly controversial among epidemiologists until now.

Once again, they argued that the economy can only be saved with generous state aid. What is forgotten is that history has shown that liberalism does not perish quickly but slowly, piece by piece.

This time, the big companies did not trigger the crisis through their reckless, risk-taking behavior. Nevertheless, they have put themselves into a more difficult situation than they would have put themselves if they had not been sure that the state and the central bank would come to the rescue again.

That ship has sailed, and many mainstream economists have encouraged this with their calls for interventionism during the crisis. Funny though, as the end of the pandemic seems to be near, those who called the loudest for government support now call to return to a more restrictive budget policy. Although many neoliberals talk about this problem in good times, they overthrow their principles as soon as a new crisis hits.

The result was equal to the GFC: Neoliberal 'rescue policy' has ensured that the wealthier part of the population has recovered and has become even more prosperous, while the broad mass of the population suffered: some lost their job, some lost their social life, at best many received 80 % of their previous wages because of government subsidies.

Those people will suffer from the consequences of those measures for much longer than wealthy people, and that is why they are frustrated and call for more government interventions. The interventionists hope to offset current debt with future economic growth will fizzle out, as it always does.

This leads me to conclude that neoliberal proponents of the third way have done nothing good to classical liberalist ideas, even though they had well-intended motives. It will be those economists who will drive the people into the arms of the interventionists (I think we will be happier to have a job rather than having protected savings - Madame Lagarde), and the liberal idea will continue its' long road to ruin, and more interventionism will lead to even more economic devastation. I am pretty sure that at some point, an allegedly temporary wealth tax will be implemented, and neoliberals will argue that it is necessary in such difficult times. And again, this tax will not be temporary as no tax has ever been.

Paradoxically, even though some people have rediscovered classical liberal ideas during recent economic crises, these have plunged liberalism, despite all its historical merits, into another crisis. Unfortunately, in their understanding of liberals, representatives of neoclassical schools are to blame for much of this.

Only when people finally return to classical liberal ideas, such that losses are also privatized, can the (temporary) victory of interventionism be prevented. Smaller, more agile companies and banks would ultimately benefit from this. Let us hope that texts like this will help to get more people excited about liberalism!

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Fabian Wintersberger

Disclaimer: This is a personal blog. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated within a professional or personal capacity.

Comments

Post a Comment