The ECBs Dilemma

This week I want to talk more about central bank policy and its consequences, especially the ECB and a possible dilemma on the horizon. Whenever ECB members talk about NIRP, they point out that the primary goal of negative interest rates and quantitative easing is to keep financial conditions favorable for the economic recovery, so commercial banks create loans to businesses to create real economic growth.

However, it seems that econometric models of central bankers (not only the ECBs models) overlook the fact that low-interest rate policies and bond buying programs do not only influence the slope of the yield curve but the structure of the real economy as well. Such policies distort the production process of an economy because it leads to the reallocation of capital. For example, capital X is invested in A instead of B, which distorts the whole supply and demand system.

I want to start today's text with a short summary of ECB bond buying programs since 2009 and talk a little bit about its mechanics (if you want to know more about it, you can read it here). Afterward I want to discuss the consequences of artificially low-interest rates and show how it influences investment decisions by businesses, and thus the economy as a whole and (usually) lead to capital consumption.

Finally, I want to talk about the latest events in the global bond market, where prices have been in free fall since the beginning of the year. Although the ECB has verbally intervened, it cannot fight market forces without risking a recurring sovereign debt crisis.

The ECB launched its version of quantitative easing in March 2015, at least officially. Although one should remember that the ECB started to buy Pfandbriefe (a specific form of a covered bond) back in 2009 already within its' covered bond purchase program to support the Pfandbrief market.

In 2012 the ECB started to buy European government bonds on the secondary market. Initially, the ECB mainly bought bonds from the periphery, Greece, Portugal & Italy. During this time, the ECB tried to keep the money supply constant by withdrawing it elsewhere. However, the ECB ended this in 2014 because of low inflation in Euro-Area.

Simultaneously the OMT program enabled countries to have government bond purchases via the secondary market, which, however, has not been used.

Since 2016 the ECB additionally started to buy corporate bonds to prop up the corporate bond market. There is the main difference between the government bond buying programs: The ECB is allowed to buy those bonds at auction. As the corona pandemic hit the world, the ECB expanded its' bond buying programs further and further.

The ECB's goal - as I wrote before - is to support favorable financial conditions in the euro economy. Buying of government bonds should have supported countries with high debt to get their house in order. In contrast, buyings of corporate bonds should encourage businesses to invest and therefore support the economic recovery.

Government bond purchases are carried out via the secondary market, which means that the ECB is buying those bonds from commercial banks and institutional investors who bought the bond in the first place. Whenever the ECB buys a bond from commercial banks, the broad money supply does not increase, and it only affects the commercial banks' balance sheets as bank reserves replace the bond on the bank's asset side of the balance sheet.

Suppose the ECB buys government bonds from institutional investors. In that case, this - theoretically - increases the broad money supply, but 1) the vast majority of government bonds are held by commercial banks and 2) institutional investors usually reinvest those revenues in the financial markets (corporate bonds or equities, for example) and not the real economy.

The appearance of the ECB as a buyer on the secondary markets leads to higher demand for government bonds, which leads to rising bond prices (lower rates). The more bonds the ECB wants to buy, the lower the yield on government bonds will be, ceteris paribus.

If yields on government bonds go down, investors look for alternatives with a higher yield. This has happened since the ECB started QE, as we can see on tighter bond spreads.

However, banks and other institutional investors like pension funds are obligated to hold a certain amount of government bonds because they are considered risk-free assets. Just because of that, there is a certain amount of base demand for government bonds, although low yields may not price risks accurately.

But there is another point: Ongena et al. found out in a paper in 2016 that European governments are influencing domestic, commercial banks actively (and successfully). Therefore they analyzed data from 60 commercial banks within the Eurozone and showed that domestic, commercial banks expanded their purchases whenever it was difficult for them to refinance at low rates.

Why did they buy these bonds if yields apparently do not reflect risks accurately? Of course, it is easier to buy if you know that there is a potential buyer of last resort.

Consequently, governments (from states where the ECB buys) face a more attractive financial environment as refinancing is less costly. Therefore one should expect that those countries expand their bond issuances because refinancing gets cheaper over time, and therefore the interest rate burden is getting lower and lower.

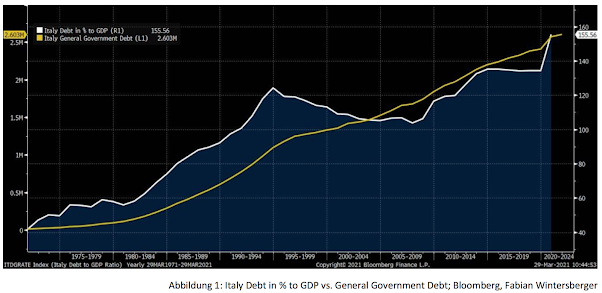

Keynesian economists always point out that the total debt amount is not relevant, but the debt/GDP ratio is not. They argue that government investments may be a tailwind for GDP growth and, therefore GDP will offset the debt. Theoretically, this may be correct, although a look at Italy shows that the argument is not valid in practice. The Italian economy has never been able to offset the debt.

The most extended period where Italy's debt/GDP ratio had been going down was from the late 1990s until the 2008 GFC. Because of the implementation of the euro, the Italian government and Italian businesses could load up on debt on unprecedented terms. During the ECB's QE program Italy has never been able to bring its debt/GDP ratio down; it just stagnated at 135 % until 2020 as debt took off again to 155 %/GDP. Germany, which reduced its debt/GDP ratio during that time, was heavily criticized for doing so by Keynesian economists.

Because the ECB kept interest rates artificially low, governments expanded debt, and commercial banks bought the newly issued debt with pleasure because they knew that the ECB would buy them at a mark-up.

The debt is pumped into the economy and invested in things like infrastructure or education. But many governments prefer to spend the money (to raise pensions or to specific groups in the vicinity of them, e.g.), i.e., in areas where the borrowed capital is consumed. So here, the ECB is missing its stated goal already.

Another goal of QE has been that the commercial banks will expand lending to support the real economy. However, the sellers of government bonds mostly preferred to invest the money into equities, corporate bonds (which pay a higher yield), or real estate.

There was another effect on corporate bonds: Because the ECB had the right to buy them at auction, businesses could also refinance at a cheaper rate and therefore loaded up on more debt than before. The recipe has been straightforward: Borrow cheap money and buy back your stock, pushing up prices. But some businesses invest into real projects, right?

The ECB's interference has caused distortions too because businesses were fooled to realize projects they may have not realized at higher rates because they would not have been profitable.

The net present value method is a standard tool to calculate whether an investment is worthwhile. One calculates the current value of expected income and expenses related to a project and pares it with the acquisition of value in which the amounts are discounted with the risk-free interest rate (if the money just lays around in your bank account). By pushing interest rates down, the ECB is getting companies to tackle projects that actually consume capital.

Imagine a business that wants to invest in a new project, Project X, which costs €300,000 initially and generates an annual profit of €38,000. In years 2, 5, and 8 a maintenance fee of €20,000 is due. Currently, 10y Bunds pay a yield of -0.3 %, but let us assume that the business calculates with an interest rate of zero.

According to the calculation, the business will invest in the project because the investment is positive. However, the reason is that it is positive because zero per cent interest rates and expected profits in 10 years have the same value as todays' profit.

But what if interest rates rise to, let us say, 2 %? Then the investment suddenly is unprofitable, and therefore capital is consumed and the business loses money. In our thought experiment, a profit of €10,000 would have turned into a loss of €22,057.15.

I wanted to show that businesses invest in projects, within an environment where the ECB is setting interest rates artificially low, which would not have been profitable without the ECB's intervention.

However, there is another part to the story: By realizing the projects, factors of production (labor and capital) are missing in other (more profitable) projects which are also profitable in a normal interest rate environment. Therefore, the ECB's intervention into interest rate markets will lead to a reallocation of capital and not only to better financial conditions. The ECB's leads businesses to make wrong decisions. This also applies to states that have invested capital they have raised on capital markets.

Now we are within an economic environment where interest rates rise globally, emanating from the US. The US is already reopening the economy, and therefore analysts expect a strong return of consumption, which was also supported by this week's consumer confidence numbers. Further, their reflation and inflation expectations are rising, accompanied by more and more calls for permanent government stimulus.

This means trouble for highly indebted countries (in the periphery) within the Euro-Area that cannot afford much higher interest rates. Higher rates would mean more difficulties for them to refinance, which as a result, may hinder the public investment that was called for by so many economists.

Of course, European central bankers know that. For weeks they have been arguing that the ECB will watch the rise in yields closely to intervene if the increase in rates is happening too from their point of view. The danger is that higher rates may stifle the economic recovery urgently needed to overcome the economic consequences of the policy measures to combat the virus.

In a Wednesday Bloomberg interview, Christine Lagarde asked if market participants wanted to test the ECB. Her answer: They can push us as much as they want. We have exceptional circumstances to deal with now, and we have exceptional tools to use and a battery of those. We will use them as and when needed to deliver on our mandate and our pledge to the economy.

Rising inflation within the Euro-Area also means a headwind for the ECB, although Lagarde, Schnabel, and others seem confident that the rise is temporary. However, while the ECB can influence bond prices and yields in the Euro-Area, it cannot control US government bond yields.

As US government bond yields rise, they are getting more and more attractive to investors in the Euro area and become an alternative to government bonds from EU periphery states. Two weeks ago, I wrote here that 10y US treasuries already pay the exact yield as Greek 10y bonds, fx-hedged, and the same is true now for Portuguese 10y government bonds.

If the ECB is fighting against rising yields within the Euro Area, it is risking that more and more investors dumping their periphery bonds, buying US treasuries instead, and hedging their FX risk. The more investors do that (and why shouldn't they?), the more bonds the ECB needs to buy to hinder a rise in rates.

Further, the ECB is risking that the euro will lose ground to other fiat currencies (or is this exactly their goal?). Additionally, another sovereign debt crisis may be right around the corner. Christine Lagarde definitely has not an easy job currently, and only a few may want to be on it instead of her. On the other hand, the ECB has caused many of these problems...

I wish you all a great (easter) weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

I wish you all a great (easter) weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Disclaimer: This is a personal blog. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations with which the owner may or may not be associated in a professional or personal capacity.

So, is not the difference between the interest rate EU governments would pay on their debts, in the absence of ECB’s government bond purchases and the decreed lower bank capital requirements, and the lower current rates they pay, not de facto a camouflaged tax?

ReplyDeletehttps://perkurowski.blogspot.com/2019/09/financial-communism.html

“Because of the Euro, the Italian government… [was] able to load up on debt on unprecedented terms”

ReplyDeleteThat’s so especially when banks even though Italy cannot print Euros on its own, and independent of its credit rating, need to hold zero capital against Italy’s debt

https://teawithft.blogspot.com/2019/06/the-still-ticking-0-risk-weight.html

“The main goal… is to keep financial conditions favorable for the economic recovery, so commercial banks create loans to businesses”

ReplyDeleteReally, with much lower bank capital requirements against residential mortgages than against loans to businesses?

https://subprimeregulations.blogspot.com/2020/12/small-businesses-like-restaurants.html

thanks for this great article..as usual economists and their theories have zero relationship with reality (ecb buys corp. bonds..corps buy back their own stock)!! question regarding the euro hedged 10-year rates..how do u calculate those. also with so much debt in the system, wat is the impact of a rising euro. is this debt short term (gov & corp)..has the euro been used as a carry trade with such low rates..therefore would we expect euro to strengthen in a risk off environment?? thnks

ReplyDeleteIf a European investor buys US-treasury bonds, his risk is that the euro appreciates against the dollar. Therefore you hedge your currency risk (e.g. with an fx-swap). A rising Euro will definitely mean trouble ahead for European exports while it may benefit companies who import raw materials and sell consumption goods domestically.

DeletePersonally I'd assume that the Euro rises in a risk-on environment (because usually in risk-off events, the dollar benefits)