The Keynesianism Of The 21st Century

The most influential economist of the 20th century died 75 years ago this week: John Maynard Keynes. His bestseller The General Theory of Employment, Interest & Money not only was a huge influence for a whole generation of economists, the book also delivered the theoretical foundation for governments to justify an indefinite rise in public spending. Government spending as an ultimate solution to fight economic downturns.

Keynes published his book in 1936, in a time where liberalism and neoclassical economic theory was in a deep crisis. Totalitarianism had spread all around Europe with the rise of Nazi-Germany and the fascist Mussolini government and Rome. Those regimes favored a centrally planned economy, an economic system that is also favored by collectivists left and right.

Keynes central thesis in the GT was the dismissal of Say's law, meaning that supply creates its own demand. Keynes criticized neoclassical economics because in neoclassical theory there is not only involuntary unemployment, only voluntary unemployment. Keynes disagreed and pointed out, that people may become involuntary unemployed in a crisis, because workers mostly do not accept lower nominal wages, even despite a (later) probable increase in real purchasing power, what he called sticky wages.

Therefore, Keynes argued, involuntary unemployment does indeed exist, which has consequences for businesses, because those people consume less. As a result (according to him) firms also start to save for a rainy day, which is causing an economic downward spiral.

Keynes proposed that the state should come in to fight this downward spiral by filling the slack in investment. He delivered the theoretical model for governments to justify more and more government spending.

After World War II, Keynesianism became the leading school of thought in both, macroeconomics and political economy, and governments started to load up on debt to keep the economic engine going. What they did not remembered was the second part of Keynes, which said, that governments should indeed pay down the debt in good times to create space for fiscal actions in downturns.

In those years, neoclassical theory and Keynesianism came together (Neo-Keynesianism) and the Keynesian framework was put into an aggregate supply and demand model. This framework is still used by a majority of macro-economists.

In the 1970s, however, countries experienced high inflation rates and during the decade, monetarists have taken over. In short: Now economic downturns should be solved by lowering interest rates to let the private sector solve its problems itself.

Since Paul Volcker became Fed chairman and raised interest rates drastically to fight inflation, lowering interest rates in an economic bust became the major recipe to fight recessions. Nevertheless, central banks always failed when they tried to raise interest rates back to pre-crisis levels which became very obvious since 2000.

Another goal - by lowering interest rates - is to bring inflation over the medium term back to close to 2 %. Nothing is more dangerous than stable (i mean really stable!) prices, not to mention falling prices according to economists at the ECB or the Fed. Keynes also meant that a smooth inflation over time may be benefitting for the majority. This is what central bankers call price stability nowadays.

Pluralist economists (especially from the left) never hesitate to call for more government engagement (ergo: increased spending), especially since the GFC in 2007/2008 hit. Their (correct) argument is that the low interest rate allocates money into asset markets instead of into the real economy.

Paradoxically in my opinion, because government expenses increase in every economic downturn. There simply is no country in the world which does something different, the only differ in size. However, modern day Keynesians think that is not enough. Economic downturns, they say, happen, because not enough money was spend after the last crisis.

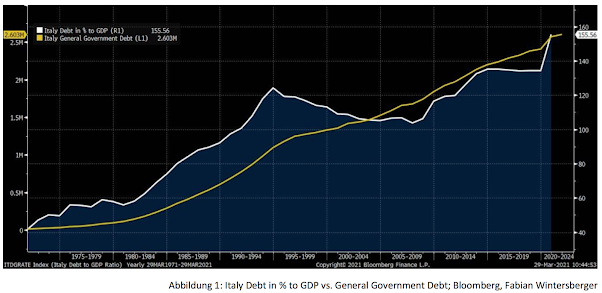

When we think about all those spending programs to fight the corona pandemic, with reference to it the argument is not valid because fiscal deficit have risen drastically like never before in history (except for war times). But still, Keynesians call for more stimulus, more government investment, more debt. Recently they blame the European governments for spending to little to fight Covid-19. The total debt/GDP ratio has increased to 200% in many countries (government debt/GDP is mostly above 90%), according to the IIF.

I do not know wether Keynes would have called for an increase in government spending at such high debt levels, but his predecessors definitely do. Even though because Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff have found out that medium real GDP falls whenever the debt/GDP ratio exceeds 90%.

This is also mentioned in another Article by Alhambra Investments' Jeff Snider and he delivers a chart where this gets obvious. Europe left its' Real GDP path in 2008 and despite massive amounts of stimulus which resulted in higher and higher debt/GDP ratios, by no chance baseline Real GDP was reached ever since.

Snider correctly notes: Obviously, the neo-Keynesians have all along strenuously objected to these findings, the mere mention that it might be possible for debt levels to subtract from growth rather than add much to it (as mainstream models uniformly assume).

Keynesians may argue that this may be correct, but we only need more government spending and investment to overcome this and to kick off growth. Europe has to follow the US and has to go BIG, they say. Well, let's look at the US then... does not look good:

Here i want to write a little bit about Modern Monetary Theory, because according to Professor Stephanie Kelton (advisor of Bernie Sanders and advocate for MMT), MMT is more Keynesian than Keynesianism (she said that in Nov. 20, 2020 at the Kreisky Forum where she was interviewed). Proponents of MMT say that we cannot afford it is the wrong approach, the right one would be do we think we should have it.

According to MMT, loans create deposits and not the other way around. However, as ZeroHedge has pointed out recently: there are now far more deposits than there are loans in the US banking system.

If you look what have may caused the difference between loans and deposits, the article gives a good guess: It may have to do something with all the Feds' bond buying programs:

The fall in money velocity is directly in relationship with all this: The newly created bank reserves have a diminishing influence on real economic output.

Everyone is talking about a future where the central bank and the Treasury will work hand in hand, but maybe we are already in the middle of it. Governments never made structural reforms when they have enjoyed low interest rates. Another wish from modern day Keynesians: We have to borrow because now we get paid to load up on debt!

However, low/zero/negative interest rates have bad consequences: Pension funds and other institutional investors have guaranteed a certain yield years before all this happened and they struggle to earn that yield. As a result their investments gets riskier and riskier which leads CCC-rated bond yields drop to record lows in times of exploding debt.

It's never been cheaper for the most financially-fragile companies to borrow money. Yields on triple-C bonds have fallen to a record low 8%, with investors mostly shrugging off the risk of default. Via ICE BofA index data & @theterminal: pic.twitter.com/X7s7TJWcLl

— Lisa Abramowicz (@lisaabramowicz1) April 19, 2021

Maybe in the short term something will be able to drive economic growth, but it is not government spendings. Because of very little possibilities to spend your money, private savings have risen sharply since the start of the pandemic.

And no, this chart does not refute Say's Law that S=I because this is true over the long term, of course there can be differences in the short term. But even this impact on GDP will not last long.

One cannot deny that Keynesian economics enjoyed a revival since 2008, after being in the background of neoclassical economics despite of never being really off-mainstream. Keynesianism was always an important part of macro-economics and never away, for example when everyone is referencing to the Phillips Curve.

What can we expect when it comes to economic policy? As I have written above, a stronger connection between treasury departments and central bank. The current crisis is a perfect scapegoat for doing this and hardly any government will be able to resist. It will be the last try to save the current system; the last try to kick the can further down the road.

The ongoing claims of Keynesians to do more of the same is just logical when you are taking Keynes' General Theory serious. Now it has to be the Green Deal, where the US and Europe need to invest and where going big, fiscal expansion should not only save the planet, but should also lead to a huge increase in employment and economic growth. If all those nice headlines will become reality? Highly unlikely in my opinion. Central planning has never worked.

Keynes is dead for 75 years now, but not so his theories. They are far more well alive than they were 30 years ago. To me it seems that, after Hugo Chavez has called his government in Venezuela the socialism of the 21st Century, there is another, new and polished idea: Keynesianism of the 21st Century.

Although those ideas are neither new nor innovative, just as this was the Keynes with Keynes' General Theory. As Henry Hazlitt wrote in his book The Failure of the New Economics:

'Whatever is original in Keynes is not true and whatever is true is not original'

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Disclaimer: This is a personal blog. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner and do not represent those of people, institutions or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in professional or personal capacity.

Comments

Post a Comment