The Last Dance

We all move inside bubbles. Most of our opinions are in line with those of the people we interact with daily. Social media shows us the articles we agree on, and on Twitter, we follow people who share a similar view of the world. It is true, everyone prefers to read things that support his opinion on the world than otherwise. Nobody likes to question his own standpoint.

Nevertheless, questioning his own point of view is something we should do regularly. Only if we do that, we can test our outlook on things and learn. Either we have better arguments to propose our standpoint or change our view if the counterargument is clearly better. It is no shame to be wrong; it is terrible to stay wrong consistently.

For today's commentary, I would like to discuss the argument, why I and the majority of my opinion-bubble is wrong, and inflation will indeed be transitory.

At the beginning of the summer, I've already discussed Jeff Snider's and David Rosenberg's arguments, who continuously believe that the recent inflationary spike will not be sustainable and the economy will find itself in a deflationary environment again.

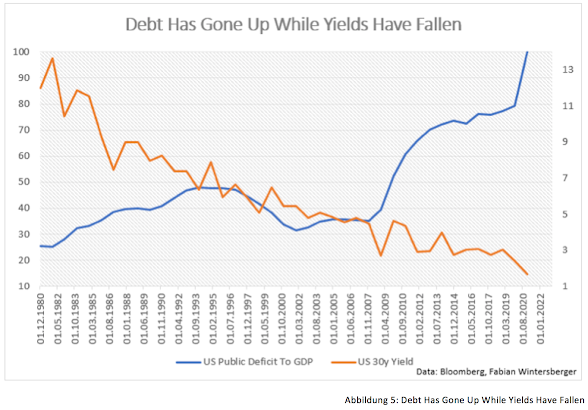

Primarily Jeff is consistently pointing to the bond market and that the bond market does not see inflation. As we all know, bond markets mostly turn out to be right when estimating future economic development. In recent days, yields rose sharply on the front end of the curve while they already started to fall on the long end. The bond market is everything but confident that inflation is a done deal and thus is weighing in on the argument of Christine Lagarde and Isabel Schnabel from the ECB instead of agreeing with officials at the Fed or the BoE, who recently stated that inflation will remain persistent for longer.

If yields rise on the short end of the curve and fall on the long end, the yield curve flattens. This is precisely the opposite of what happens if the market is expecting a pick-up in inflation. If market participants expected inflation, they would buy short-term debt and sell long-term debt because they demand higher yields for longer-duration bonds. As a result, the yield curve would steepen. It reminded me of 2017 when the Fed raised rates because they expected a pick up in inflation as the economy recovered and the labor market got more robust.

In March 2017, the Financial Times wrote: The US central bank has raised short-term interest rates for only the third time since the financial crisis, stepping up the pace of tightening as policymakers grow increasingly confident that America's enduring recovery will lift inflation.

However, the bond market considered this wrong, and the yield curve flattened for the rest of the year while inflation remained subdued. The same phenomena can be observed today: The market may think that central banks are making a mistake!

Are there reasons to think that inflation is transitory and we will return to a deflationary economic environment? Lacy Hunt (Chief Economist at Hoisington Investment Management Company) has called out the deflationary climate since the 1980s. The recent reaction from monetary- and fiscal policy has not led him to change his point of view.

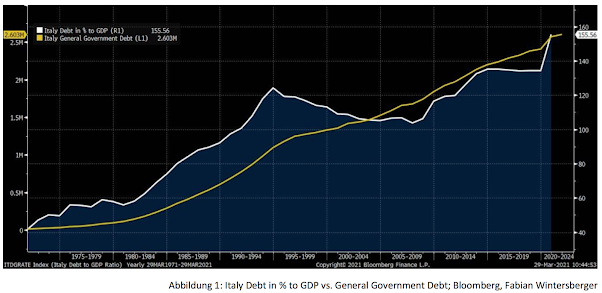

One argument that Lacy is constantly bringing up is the high level of indebtedness. As we all know, public and private debt has exploded for 40 years now, but economic growth remained surprisingly weak (at least from a Keynesian perspective). The marginal productivity of debt has diminished. Thus every additional increase of monetary units (=debt) has had fewer and fewer effects on economic growth.

Further, Lacy argues that the explosion of debt since the start of the pandemic will only lead to a continuing diminishing of the marginal productivity of debt. Vast sums of debt flow into the realization of unproductive projects, thus hindering the completion of more important projects. If the money supply is rising faster than GDP, the velocity of money comes crashing down. And this is precisely what has happened since the dot-com bubble popped.

According to Lacy, more and more debt leads to weaker and weaker growth, and thus velocity continues to fall and, as a result, so will interest rates. Therefore, he continues to believe that the deflationary environment will resume soon. Policymakers have tried to solve the debt problem with more and more debt for several years now. But as the marginal productivity of debt diminishes, the problem will not be solved.

It is hard to dismiss Lacy's argument if one compares the US debt/GDP ratio with government bond yields. Moreover, it is nearly impossible to do so. The debt/GDP ratio has increased rapidly after 2008 while 30y US bond yields crashed.

The following chart is from Hoisington's Q3 report, where Lacy compares real GDP development with its pre-2000 trend. Here it becomes apparent how weak the effect of additional debt has been on real GDP.

The chart shows that Real GDP, has it followed its pre-2000 trend, should be about 25 % higher than it really is. A clear sign for diminishing marginal productivity of debt. This clearly shows that neither the Biden infrastructure plan nor the EU Recovery plan will have the intended outcome. The Keynesian chimera that a country can grow out of its own debt seems clearly debunked.

Very interesting is what, according to Lacy, would need to happen that he changes his standpoint: If central banks get the allowance from governments to spend instead of to lend. Handing out money to the government and the people directly clearly would be inflationary. However, Lacy does not think this will be the case shortly; therefore, he sticks to his deflation argument. Also, an austerity program would mean Game Over.

I think that Lacy's argument is obvious, and it is hard to argue anything against it. The question is: What happened to all the additional debt? Readers of this commentary will know the answer already. The money has flown into asset markets and drove up prices there, just as Richard Cantillon predicted about 300 years ago.

If we run a simple linear polynomial regression to investigate the relationship between money velocity and the S&P 500, this becomes obvious. I was stunned by how clear the relationship was.

While I agree with Lacy's analysis of the past, how western economies got into the current situation that they are now, I still am not convinced that deflation will return anytime soon. I think that inflation will not return to pre-crisis levels.

Firstly, I think that supply-chain disruptions will sustain for longer than we think, and several CEOs of various companies have already made that point. Ships are queuing in front of US Ports, as the Financial Times has reported lately: The queue of ships stacked high with brightly-coloured containers reached a record of 73 anchored container ships on September 19 and by last weekend still stretched as far as the eye could see — frustrating retailers and becoming a national symbol of an outdated and overwhelmed US supply chain.

Additionally, the China-Taiwan conflict is getting more and more severe. Xi Jinping has made it clear that China's goal is to annex the island in the South China sea. According to the European Institute for Asian Studies, more than 60 % of all semiconductor chips are produced in Taiwan. One can only imagine the consequences of something like a sea blockade by the Chinese on the market.

Meanwhile, German Automakers and machine builders are sending their workers to Kurzarbeit again. In the Kurzarbeit scheme, workers get paid more-or-less (about 80%) the same while they work substantially shorter (partly only 20 %).

Magnesium is an essential part of auto production and for the production of aluminum. And it is not only semiconductor chips: Recently, the economy has experienced magnesium shortages too. Due to the energy crisis in China, the production of magnesium has fallen. It is expected that China will produce 10 % less magnesium this year.

However, the Energy crisis has relaxed in Europe, since Wladimir Putin stated that Russia will now send more gas to Europe to fill up storages there. But US's and EU's plans to push the green transition forward may lead to further inflationary pressures.

To reach their climate goals, European countries and the United States want to make oil usage unattractive. Therefore, they plan (and some already have) to give CO2 a price that should rise steadily. While the intentions are clearly honorable, they neglect that CO2, energy, is part of every production process. Energy is a crucial cost factor. If one artificially bids up the price of CO2, consumer prices will follow. As a result, pricing CO2 IS inflationary on its own.

Furthermore, a higher CO2 price is an over proportional burden for low-income groups. How countries are already trying to counteract this does not bode well: Additional transfer payments will literally (and quite appropriately) continue to pour fuel into the fire and drive prices up further.

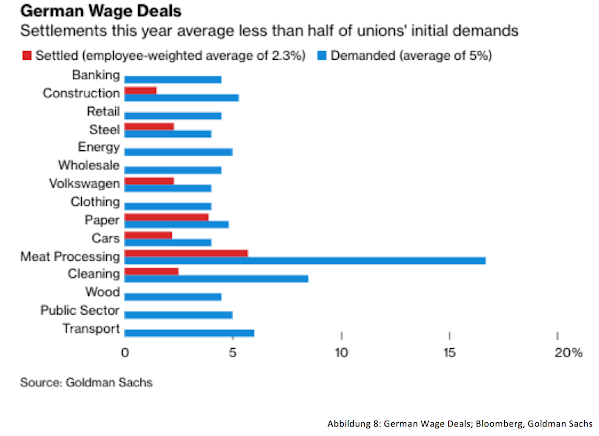

As a result, workers may demand higher wages, and thus a dangerous wage-price spiral will emerge. However, at least in Germany, this does not seem to be the case for the moment: Wage increases remained well below union expectations.

Another point for a continuing climb of inflation rates is that spiking producer prices are just starting to find their way into consumer prices. However, the US enjoys the appreciation of the US dollar to cope with the rise in Chinese producer prices.

In the meantime, stock prices have rushed from one sugar-high to another, not very impressed by prospects of future rate hikes or tapering from central banks. Is this already the final crack-up boom?

Finally, there is one more argument that inflation will persist: American states are already rolling out new waves of transfer payments. For example, Los Angeles:

JUST IN: Los Angeles to pay $1,000 a month to 3,000 families in new guaranteed-income program - CNS

— Breaking911 (@Breaking911) October 26, 2021

And there is a high probability, that the Biden administration will also push for another round of stimulus, according to French economist Christophe Barraud:

🇺🇸 There is a high prob. that Biden administration pushes for another stimulus check this winter (ahead of midterms) as the most fragile households will face a huge inflationary shock YoY:

— Christophe Barraud🛢 (@C_Barraud) October 27, 2021

*Food: ~+5%

*Gasoline: >+30%

*Heating Bill: >+30%

*Rents: >+10%https://t.co/tSwxOXVQWO

Because of that, I think that the deflationary camp is wrong. Apart from central banks, which pump vast sums of money (or bank reserves) into the system, governments are already beginning to hand out money to the people (or (some sort of) 'Peoples QE', as Andreas Steno Larsen put it once).

Once we reach a tipping point, I think it is not unplausible that money velocity in the real economy will pick up again while money velocity in the financial economy is falling. We can make similar observations when looking at what happened in Weimar Germany: If money is rushing back into the real economy, you cannot stop it.

The more important question is: Will this event happen soon, or are we witnessing one final, deflationary shock? Or will governments and central banks be able to manage to kick the can down the road even further? Many people have called several of the last downturns the final crash, and, at least until now, they have been consistently wrong.

Personally, I agree with Russel Napier's theory (I wrote about it last week here): Inflation is here to stay, and institutional investors will be forced to buy bonds to lose money in real terms.

Finally, there is (maybe) something good: The average Joe and Jane will experience the final crash (if there really is one) the same way as people who watched the fall of Ancient Rome: After a short time, they will soon forget that it happened.

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Disclaimer: This is a personal blog. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner, and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with within a professional or personal capacity.

Comments

Post a Comment