Potpourri

This week's commentary will be a potpourri of several topics that I've come across this week and caught my attention. And, of course, because I am writing from the first country in Europe that returns to complete lockdown again, I have to start with corona.

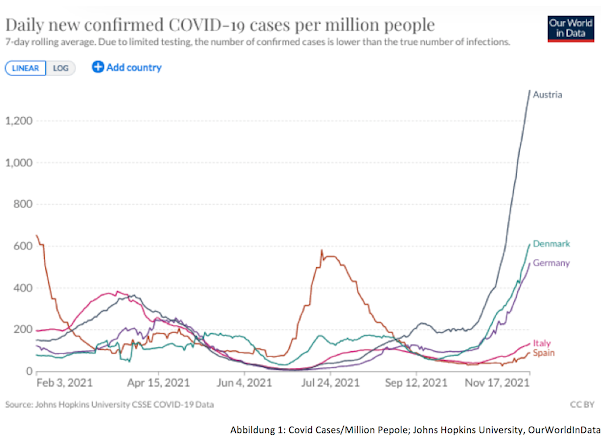

Many people were fearful of it, and so did it happen. Corona is back in Europe, especially in the German-speaking area. Austria is on the top when it comes to new daily positive test results, and, as media outlets report, a collapse of the Austrian health care system is imminent. Yesterday (Nov. 18th), Upper Austria and Salzburg declared to return to total lockdown (vaccinated and unvaccinated) for at least two weeks. The rest of Austria will follow soon, and so will Germany.

Of course, pushing for a higher vaccination rate of the population will not help to relax the situation soon, but over the medium term. However, over the long term, it is still uncertain, as we see in other countries. Even those with high vaccination rates face a rise in positive test results and thus are on the edge of implementing restrictions again. Denmark, for example, has lifted all restrictions a few months ago because of its high vaccination rate, but as infection rates are on the rise again, the country has reversed course. What is puzzling, in my opinion, is that again, there is no talking about side-effects of such measures (economically and from a psychic health standpoint) and that politics has failed (again) and is now claiming that the new steps have no alternative.

The vaccine efficacy of allegedly 90 % vanishes over a few months, as recent studies show. You cannot get covid if you have the vaccine (a sentence from Joe Biden) has been proven wrong. If there is any protection from spreading it, it only lasts about two or three months. Further, the news that even 'boosted (vaxxed a third time) patients can catch covid is not promising that a third shot will prevent spreading. Let us hope that the protection of having a severe case holds on longer. Currently, it seems that at least this statement is valid.

The uncertain situation in Europe weighs against the euro. EUR/USD, above 1,20 USD in July, has fallen further and further and now is below 1.14 USD. Further, the ECB is still arguing that the time is not suitable to think about raising interest rates in 2022, while the market expects that the US Fed will hike rates at least two times in 2022.

In 2012, US 10y treasuries had the more-or-less the same nominal yield as the 10y German Bund. However, after Draghi's Whatever it takes - speech, they both have decoupled. Even this year, the different path is obvious: While US 10y has risen from well under 1 % to slightly under 1.60 % this year, the 10y Bund yield has traded mostly sideways.

Low yields have in Europe have been a problem for quite a while now. Although US and European banks' recovery has been the same after the 2020 downturn (they both have roughly doubled), the Eurostoxx banking index is still at the same level as it was in 2011. In my opinion, that is a result of a) zero percent interest rates (lower revenue), and b) more and more regulation that is driving up costs.

On the other hand, equity markets continue to make new highs this week, despite lots of small stocks in the red this week. However, equity traders are taking more and more risk, as this beautiful chart by TopDown Charts shows:

Is this a sign that the stock market rally is over? I do not think so because earnings are still strong & the (US) economy is still expanding, and thus I expect the rally to continue at least until Q2 of 2022.

However, there seem to be some warnings from the bond market. While the VIX is still very low, the MOVE has reached a level last seen in spring 2020. In my opinion, a possible sign that the market is expecting the Fed to make a mistake.

I have written about it several times before: The yield curve is flattening, with 20s30s inverse. The strong dollar pushes demand for US treasuries. I expect many analysts to be proven wrong, and the US 10y will not reach 2 % this year. My argument is that the market expects that the tapering will not last very long and therefore tries to front-run the Fed.

Let me now turn to another topic. The European energy crisis is still not solved, despite Putin's promise that gas will flow to Europe now. On the one hand, because there was hardly any gas flowing and on the other hand because European gas prices started to rise again after the Financial Times wrote that the German energy regulator temporarily suspended Nord Stream 2.

The reason, according to the article: The regulator said it could not yet approve the project, led by Russia’s Gazprom, because its owners had chosen to create a German subsidiary branch that was not yet properly set up according to German law.

Isn't it ironic, don't you think? Much needed natural gas will not come to Europe because of German bureaucracy.

This brings me straight to Brexit. Do you remember all the comments about how bad it will hurt the UK, how companies will exit the UK and locate their headquarters in the EU? Well, surprise, neither banks moved their staff to the EU, nor did many other companies relocate. On the contrary, countries move to the UK. The latest example: Shell, or former Royal Dutch Shell.

Shell's exit of the Netherlands is due to heavy environmental regulations and thus a result of Holland's policy. But instead of rethinking its policy, dutch opposition parties are now arguing for an Exit-tax (the same happened to Unilever when they closed their NL headquarter).

Finally, I want to touch on another topic in this commentary, although I get tired of writing about it: Yes, of course, it's inflation.

Firstly I want to share a chart and argue that inflation is not only a problem of supply-chain disruptions because if that was true, Switzerland would also have a high inflation rate. Inflation was always a monetary phenomenon: If the supply of money expands faster than the supply of goods, prices rise. However, Switzerland's inflation is much lower than in the US, Germany, or the Eurozone.

And another thing has caught my attention recently: More and more articles about why inflation is good for you. I have written about an MSNBC article already, arguing that this time inflation is good because of all the government transfer payments.

Jon Schwarz, however, has made up another hilarious argument in The Intercept: Inflation would benefit the average household but hurt the one-percenters. Schwarz writes: And what’s happening is this: The inflation freakout is all about class conflict. In fact, it may be the fundamental class conflict: that between creditors and debtors, a fight that’s been going on since the foundation of the United States. That’s because inflation is mostly good for most of us, but is terrible for [the rich].

What a good thing inflation is, is it not? While his first argument is that inflation lowers the real value of debt and thus benefits households with high debt, his second argument is that inflation is bringing down unemployment and a sign of an economic boom.

Regarding the second, I would argue that this is not always the case and that the Philips Curve was debunked a long time ago, despite some workarounds within the model by economists. Remember the boom of the 1970s? No? Well, because there was no boom despite high inflation.

The first argument looks more compelling but is even more bizarre. Even if it is true that inflation brings down the real value of debt, it definitely does not mean that it hurts the one-percenters.

Because of low-interest rates, high-income households could load up on cheap credit to buy more assets because they already had many assets in possession. If inflation kicks in, their real value of debt (which is mostly much higher than the average household's debt burden) decreases while the prices of their assets increase. They used their assets as collateral to buy more assets, while low-income families could not even save at least something to buy a home at an artificially high price.

Inflation is always worst for low-income households because they have to spend a higher proportion of their income to buy those goods than high-income households. It is nothing more than a bad joke to argue that inflation is benefiting low-income households.

The last time inflation was above 4 % in the US was in 2008, during the GFC. The wealth gap, however, narrowed just as deflation kicked in.

Further, this chart shows how QE widens the wealth gap despite central banks still denying it. Although, not as much as one year ago.

Have a great weekend, everyone!

Fabian Wintersberger

Fabian Wintersberger

Disclaimer: This is a personal blog. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner, and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with within a professional or personal capacity.

Comments

Post a Comment