The Cobra-Effect

Have you ever heard of the Cobra-Effect? It describes how a certain measure to solve a specific problem leads to various unintended consequences, worsening the situation.

The effect was firstly described by German economist Horst Siebert's book The Cobra-Effect, who used the analogy to show the consequences of wrong economic incentives, or put otherwise: Well meant is poorly done.

The story Siebert told goes like this (and I am not sure if this actually happened): Back in the days when the British Empire was reigning in India, the country suffered from a vast plague of cobras. A local British governor tried to solve this problem and offered a premium for every cobra delivered to local authorities.

In the beginning, everything went according to plan: People started to hunt cobras and delivered them to the authorities. However, after a brief period, the government found out that the total amount of cobras had increased instead of decreased.

How so? In prospect of income, people started to breed cobras to kill them to receive the offered premium. When the problem was detected, and the measure was halted, those breeders released the snakes because they had no use for them anymore. In the end, the number of cobras in India was higher than before the measure was introduced.

A similar phenomenon (and proved historically accurate) was the bounty program of french occupiers in Vietnam. They offered payment for every rat-tail delivered to get rid of a rat plague there. There, people started to simply cut off rats' tails to let them run afterward, and as a result, the rat population continued to increase.

Similarly, economist Ludwig von Mises described the phenomena (later known as Oelfleck-Theorem) to sum up the unintended consequences of - often well-meant - policy measures that apparently solve a problem but cause a lot of economic difficulties beneath the surface.

In December 2017, CNBC titled: Janet Yellen's only regret as Fed chair: Low Inflation. Although the Fed tried everything it could, through zero percent interest rates and QE, it could not raise inflation to its target of 2 %.

Meanwhile, Janet Yellen has become the secretary of the treasury. Still, together with her predecessor Jerome Powell, she may have finally achieved what she did not succeed during her reign at the Fed: Higher inflation!

If you are a continuing reader of my commentaries, you know that this is not surprising. Since I have started my writing, I have written about the dangers of this kind of monetary and fiscal policy. Although I have to admit that several current problems of the economy contribute to inflation, such as supply-chain disruptions and rising energy prices, we should not forget that inflation is always a monetary phenomenon everywhere.

Like Nobel-laureate Paul Krugman, many celebrated the win of team transitory after last month's inflation numbers. The inflation numbers that were published this week may be a counterargument to theirs. In my opinion, they show that inflation will not go away soon.

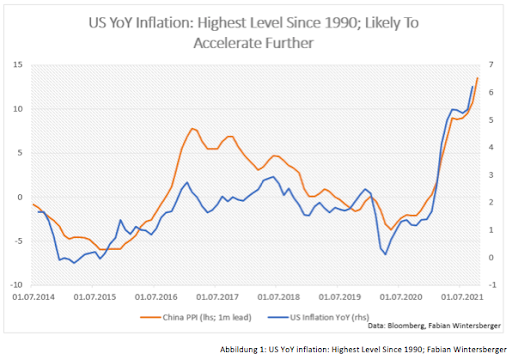

Year-on-year inflation in October was at 6.2 %, month-on-month inflation .9 %. Core values are still 4.6 % year-on-year, or .6 % month-on-month. This means that inflation is running as hot as in 1990, and continuously rising producer prices in China may point out that this still is not the top for inflation.

The S&P 500 also fell about .9 % on Wednesday. 10y Treasury yields spiked as well after the numbers came out and are now back above 1.50 %. However, the yield curve flattened further. It seems that the market is still expecting that inflation will not be alive for too long.

On the other hand, the sell-off in bonds and stocks also coincided with the news that Chinese property developer Evergrande is allegedly on the edge of default. Although it turned out that this news was not accurate, bond markets have seen a high probability of a default for quite some time now, as Evergrandes USD-bonds trade between 25-30 % for quite a while.

However, let us go back to inflation. Some commentators think that high inflation numbers are a sign that the US economy is still booming. I am doubtful about that, especially when I look at the US trade deficit. Since the pandemic has started, the trade deficit has exploded, which means that the US is highly dependent on imported goods and services, especially from China. In exchange for these goods, the US exports its most important product: The US dollar.

Additionally, there is another sign on the horizon that the world economy may slow down very soon, apart from those already discussed. Chinese Credit impulse is still negative, pointing to weaker economic activity.

I stand with my forecast that we will most likely move into a stagflationary scenario because price pressures have increased recently.

Nordea (Helene Østergaard and Andreas Steno Larsen) has published 5 charts this week on why US inflation will remain high. They expect that core inflation will rise to above 5 % until New Year's Eve. According to them, wage pressures will increase (one cause being the imposed vaccine mandate by the Biden administration), rent prices, used vehicle prices, and food prices will continue to go up.

If Nordea is correct, then pressures will elevate for the Fed to hike interest rates since the general assumption is that the Fed can fight inflation through higher interest rates.

Nevertheless, last week I stumbled upon an article by Joseph Wang, a former Fed trader, questioning this assumption. Let us remember what I wrote above about the Cobra-Effect.

The Fed has increased the number of bank reserves in the banking system through QE in order to increase inflation. Regarding the last decade, it is easy to say that they have failed miserably. Wang's argument is fascinating: Similar to the Cobra-Effect, the Fed may have turned how the plumbing works upside down.

Wang argues that rate increases will cause a rise in bank loans because banks have shifted their funding structure from money market funding to retail deposit funding due to Basel III and the enormous increase in retail deposits. As a result, banks are less reliant on money market funding.

Due to QE, banks have enormous bank reserves, as intended by the Fed and its QE program. Further, transfer payments from governments to fight the economic consequences of the pandemic have led to a vast increase in US retail deposits (about 5 billion US-Dollars). Wang writes: Retail deposits are the cheapest source of funding available to a bank because retail depositors are willing to receive 0% interest even when market rates are much higher. Bank lending decisions are shaped more by their opportunity cost (IOR), than their funding costs.

Let us have a closer look: After 2011, although rates increased, rates for retail deposits did not do very much because they did not need to compete for cheap deposit funding because they have had (and still have) an abundance of bank reserves. So, although the Fed hiked, retail-deposit rates stayed close to zero percent.

If the Fed increases interest rates, the reverse repo rate will rise and may lead to a reshift from retail deposit funding to money market funding. However, as a chart from Wang shows, the shift was just taking place during the last hiking cycle as rates rose to 2.5 %. Wang expects that, according to the significant increase in retail deposits, rates would have to increase much more today to cause this.

Further, another catch is that: According to a recently published report by JP Morgan, a 1 % increase in rates would lead to increased revenue of 6 billion dollars. Thus, we can assume that rate hikes will positively affect bank revenues but, on the other hand, will not do much for deposit rates.

In return, let us assume that the banks will now park bank reserves at the Fed to earn the higher rate of interest through reverse repo. This additional income needs to be reinvested, for example, into US treasuries.

However, the US treasury will not issue as many treasuries as last year, and the Fed has not stated that it plans to shrink its balance sheet anytime soon. As a result, if the banks want to reinvest their additional gains into US treasuries, they have to buy them from non-banks.

If demand from banks for US treasuries rises, bond prices go up (or yields go down). If they buy treasuries from private investors, the quantity of money in the real economy goes up. Further, if private investors purchase tangible goods and services instead of reinvesting them into stocks, demand for those goods and services rises. More money in the real economy, chasing the same amount of goods and services, raises prices (=inflation).

Nevertheless, one may argue that the banks may decide to increase lending instead of buying treasuries because they can expect more revenues from lending than from buying treasuries. But this would also be inflationary. Moreover, this may lead to the result that banks lower their lending standards to boost loan creation.

However, if demand for longer duration bonds increases in such an environment, this leads to a flatter yield curve. Again, back to Joseph Wang, who writes: The new dynamic suggests rate hikes lead to a flatter yield curve, lower nominal rates, and potentially higher inflation through increased credit creation.

Finally, such a scenario would also mean trouble for stock prices: Typically, the average fund manager owns a portfolio of 60 % bonds and 40 % stocks. However, as yields went down, many started to leverage their bond-buying to increase earnings. If rates rise, they may now face a situation where they have to sell stocks to fulfill their margin obligations (let us think of what happened in March/April of 2020). As a result, the Fed would have to intervene again, may it be CBDC and thus people's QE or by starting to buy equities to bid up the stock market.

While this may solve the problem above the surface, it may lead to many harmful, unintended consequences below the surface, and the Cobra-Effect will come into motion again...

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Disclaimer: This is a personal blog. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner, and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with within a professional or personal capacity.

Comments

Post a Comment