Recep's Magic Money Tree

Recep Tayyip Erdogan was born on February 26 in Istanbul. According to him, his family immigrated from Georgia to Turkey before he was born. In his youth, Recep was religiously shaped and visited an Imam-Hatip school (a religious high school) after he finished elementary school. His deeply religious beliefs are shaping his views until today, and even his views on monetary policy have become more and more spiritual these days.

Erdogan started his political career in the 1980s, where he became heavily engaged within the National Welfare Party. One decade later, in 1994, Erdogan became mayor of Istanbul (which was mostly seen as a surprise), and after being imprisoned in 1998, he became prime minister of Turkey in 2003. On August 10, 2014, he was elected president for the first time.

When Erdogan became prime minister, Turkey suffered from a decade-long lasting economic and currency crisis. He promised the Turkish people that, if they elect him, economic mismanagement and recessions would be a thing of the past.

His first years as prime minister were a great success: Poverty and unemployment fell drastically, and inflation fell from triple-digit territory to only 5 %. Economic growth mostly stayed within a 5 to 10 % range during that time and attracted an enormous inflow of foreign capital into the country.

Erdogan was untouchable.

However, the struggles began in 2013 as Turkey suffered from the same economic problems as all other emerging economies when advanced economies regained strength. In Turkey, people started to protest against their own government and caused some political tension. As a result of this, foreign investors began to pull off capital from Turkey and thus caused trouble for the Turkish lira.

Erdogan's standpoints on economic policy have changed over time: After he brought Turkey on a path of austerity in the early 2000s, the Great Financial Crisis led to a paradigm shift.

At first, the crisis also had some good side-effects: In the years after, Erdogan attracted even more foreign capital than before the crisis. Fueled by easy money, Turkey started to invest heavily in construction, and the country enjoyed an economic boom. Hence, Erdogan was able to expand his political power.

The government's stimulus programs during the 2000s and substantial current account deficits were the main reasons. However, protests in Gezi Park in 2013 (because of the economic downturn and the Fed's hint to end its QE program) and the failed coup in 2015 led to a revival: The value of the Turkish lira started to erode again. As we all know, every artificially created boom results in a bust.

Political and economic turbulence led to a fall of foreign investment and a pull off of foreign capital from Turkey. Yields of Turkey's dollar-denominated debt spiked, and 10y yields rose from 10 to 20 %.

Nevertheless, Erdogan was not willing to understand that this was caused by his own economic policies. Instead, he blamed foreign speculators for it and started to fight the Turkish central bank, which wanted to fight the rise in inflation by hiking interest rates.

On the contrary to what the Turkish central bank did, Erdogan stated that interest rates in Turkey will fall again after he was reelected in 2018, which only led to more outflows of foreign capital and another depreciation of the lira. Even Turkish citizens started to change their savings from lira to US dollars, and thus the Turkish currency got under pressure even further.

After US-president Trump imposed tariffs on Turkish products, inflation in Turkey continued to climb, and the Turkish central bank had to provide emergency liquidity to domestic banks to calm down markets.

However, inflation did not care and was fueled further by interest-rate cuts from the Turkish central banks, despite Erdogan's claims that this will reduce inflation (remember president Biden's claim that building back better will reduce inflation?). The collapse of Turkey's currency reminds Argentina's fate, which was also hit by a currency crisis between 1998 and 2002.

Turkey is another example of why the Modern Monetary Theory is not a solution but a problem.

Proponents of Modern Monetary Theory claim that monetarily sovereign countries which spend, tax, and borrow in a fiat currency that they fully control, are not operationally constrained by revenues when it comes to federal government spending (Investopedia).

However, the fate of Argentina and Turkey show that these claims are untrue. One might argue that neither Argentina nor Turkey borrowed in their own currency but US-dollar to attract foreign capital. But this is not how it works as this well-written article by Daniel Lacalle shows. In the text, Daniel points to a study from the Bank of Canada, which identified 27 countries involved in local currency defaults between 1960 and 2016.

Even if the United States issue MMT, the rise in inflation will lead to the situation where foreign investors, or investors in general, may not be willed to accept debt issued in US-dollar. Let us take the example of Turkey: Turkey did not issue debt in its own currency because foreign investors were not willing to buy it, but they accepted debt issued in dollars. They were unwilling to take the foreign exchange risk because history has shown that a significant depreciation of the Turkish lira could not be ruled out.

Monetary sovereignty is not caused by the state. Daniel writes: Confidence and use of fiat currency are not dictated by the government nor does it give said government the power to do what it wants with monetary policies. Citizens all over the world have stopped accepting the government-issued and denominated currency when confidence in its purchasing power has been destroyed after increasing the money supply well above its real demand.

That is precisely why Argentina and Turkey failed: The people (domestic and foreign) lost trust in the currency and started to demand other currencies. An expansion in the supply of money by the central bank combined with falling foreign and domestic demand only worsens the problem.

Hence, even the United States would not be able to show that MMT is practical. Maybe there is a short period where it works, but at some point, reality would kick back in, and the dollar would suffer the same fate as the Turkish lira, the Argentine peso, or the Venezuelan bolivar.

The lack of confidence in its own institution causes citizens of a country to put their savings into other currencies where they have more trust in the institutions.

Even a world currency would not solve the problem because there are still money-substitutes like gold and crypto-currency, which are not under the direct control of governments. Abandoning them would not solve the problem either because people would start to increase demand for all goods in expectations of a continuing rise in the supply of money. People will try to spend their money as fast as possible (Gresham's Law).

One may argue that there has been a massive monetary expansion for quite a while now, and the dollar still has not lost value compared to other fiat currencies. However, that is too shortsighted: On the one hand, because all central banks are expanding their supply of money, and on the other hand, because demand for US dollars is artificially elevated because of foreigners with a lack of trust in domestic central banks. The result would be more inflation and a further debasement of the currency.

Measured in Gold, for example, the stable US dollar has lost about 9 % annually. However, the falling gold price during 2012 and 2019 was caused by the confidence of markets that the Fed could normalize its monetary policy. In retrospect, a big misconception.

Debt is not an asset because governments say so. Debt is an asset if there is demand for it. In the case of Turkey, one can witness what happens if the demand for government debt decreases. Even if the Turkish central bank would buy the debt directly, it would only result in more currency depreciation and inflation.

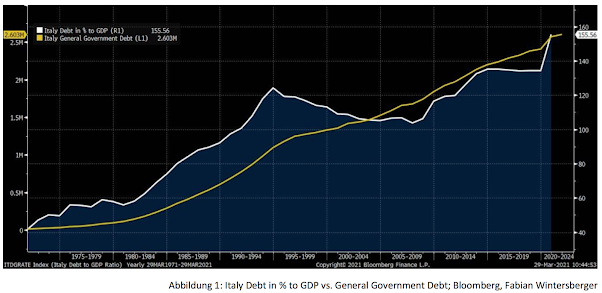

By the way, expansionary monetary policy is already harmful, even without the implementation of MMT: More debt leads to less growth, a more leveraged economy, and to a higher probability of an economic crisis. Solving an economic downturn through more expansive fiscal and monetary policy exacerbates the problem. Thus, it is no surprise that the likelihood of a financial crisis has increased since the 1970s.

Modern Monetary Theory is, as Daniel Lacalle correctly writes, fake economics. The theory was proven wrong in practice and theoretically a dozen times since it was firstly formulated by Georg Friedrich Knapp at the beginning of the 20th Century.

The last argument I want to debunk here is that every government debt is a surplus for somebody else. Therefore, people like Stephanie Kelton argue that government debt has a positive effect on economic surplus. It is a bookkeeping argument.

On the one hand, this is wrong because more government investment leads to a crowding out of private investments, mainly if governments can borrow at zero percent interest rates. If an investor cannot expect a return for his investment, he will not realize it and invest his capital somewhere else where he can expect a higher return. A businessman may not reinvest his profits into his business to buy a new machine, but invest it into other assets and let the state make the investment because he knows that the state will have the interest to invest for him, for example, if the state's goal is to reduce unemployment.

Additionally, this is another reason why it is not that easy as bookkeeping may suggest, and one's debt is not automatically another one's surplus, especially in an economic sense.

Even if there is no constraint of money because the state issues are: resources are. Land, labor, and capital are scarce. Thus, every investment decision influences the realization of other projects. For example, if the state decides that it wants to build more harbors (because of supply-chain disruptions) and intends to expand the number of truck drivers for delivery, it needs to provide the infrastructure for that. It requires construction workers, people to drive trucks, and people who produce all the materials required. To do that, the state needs to use a variety of factors of production, which are not available for the realization of other projects, like building schools, roads, or factories.

Let us assume that because of this, output in other industries falls drastically (just to underline the argument) because of a lack of factors of production. Then, the workers engaged in these projects may have monetary income on their bank accounts, but they cannot buy as many goods as before. If one cannot buy goods with your surplus, then all of your surpluses are worthless, and MMT turns out to be another monetarist fairy tale.

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Disclaimer: This is a personal blog. Any views or opinions represented in this blog are personal and belong solely to the blog owner, and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with within a professional or personal capacity.

Comments

Post a Comment